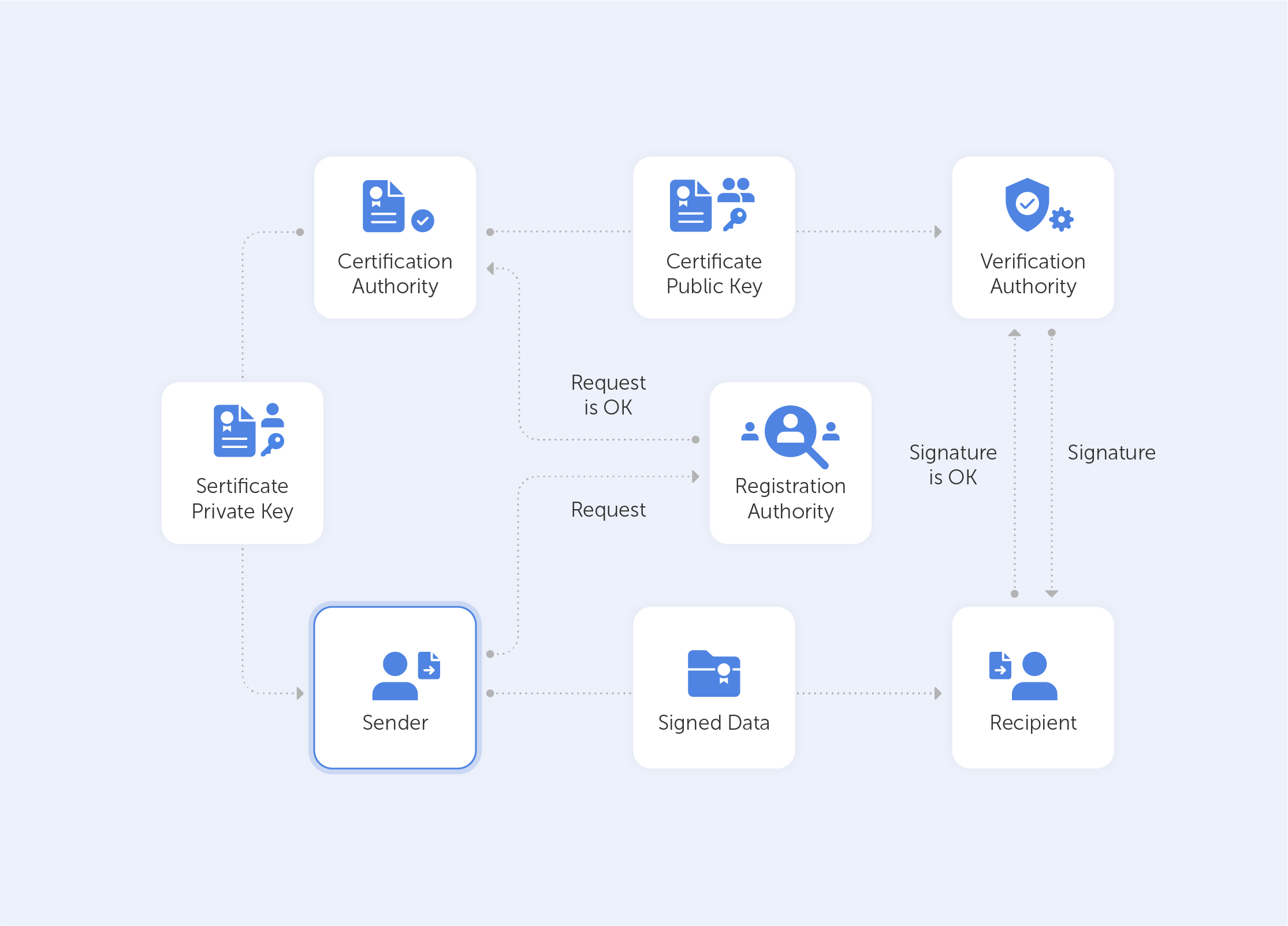

Many times, we’ve mentioned self-signed certificates and their most common use cases in our blog. After all, the main difference between a regular certificate and a self-signed one is that in the latter case, you act as the CA (Certificate Authority). But there are a variety of services that provide CA services for free, with the most popular being ‘Let’s Encrypt’, which is going to be the subject of this article.

What’s that?

‘Let’s Encrypt’ is a free certificate authority developed by the Internet Security Research Group (ISRG).

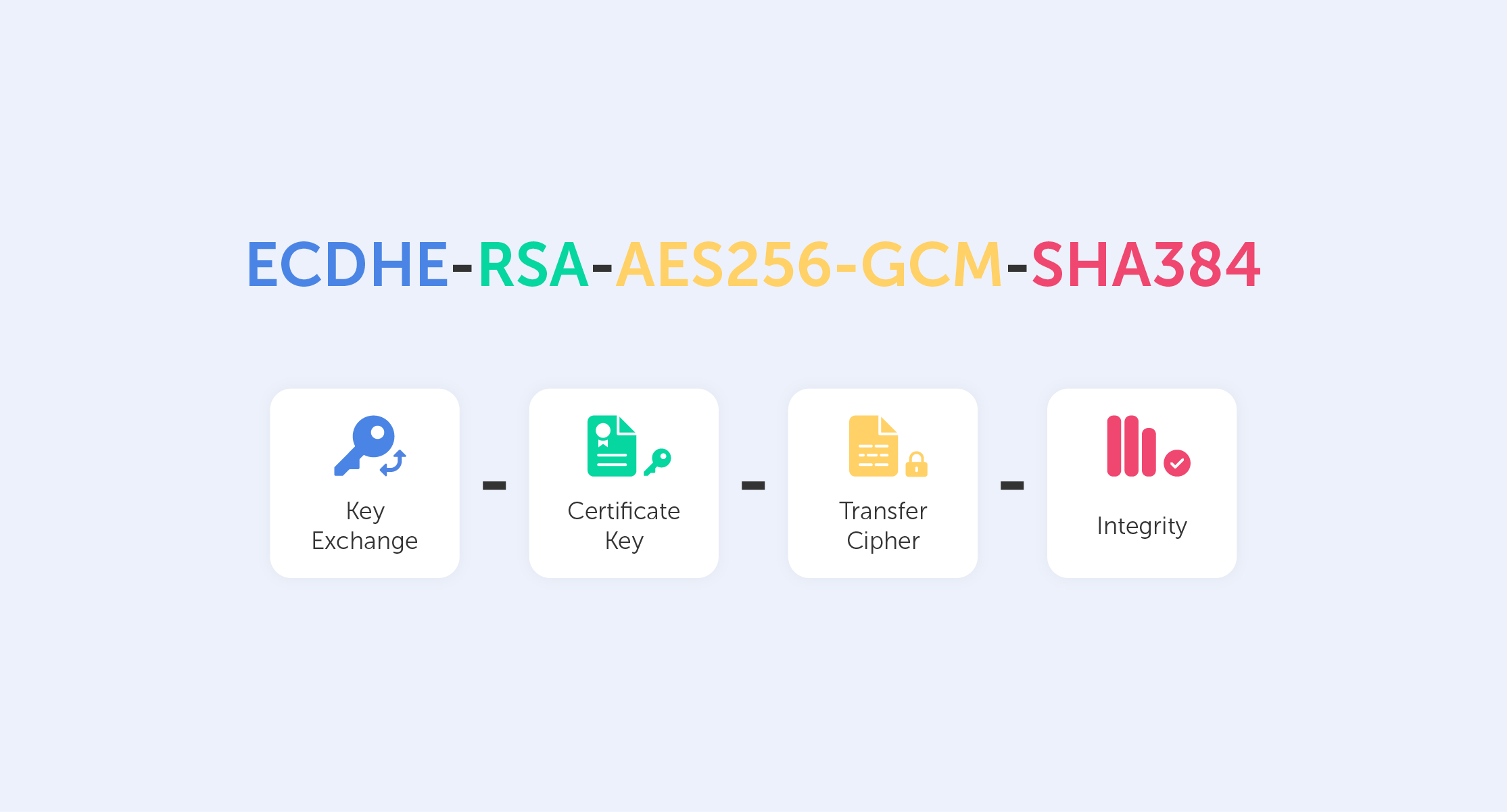

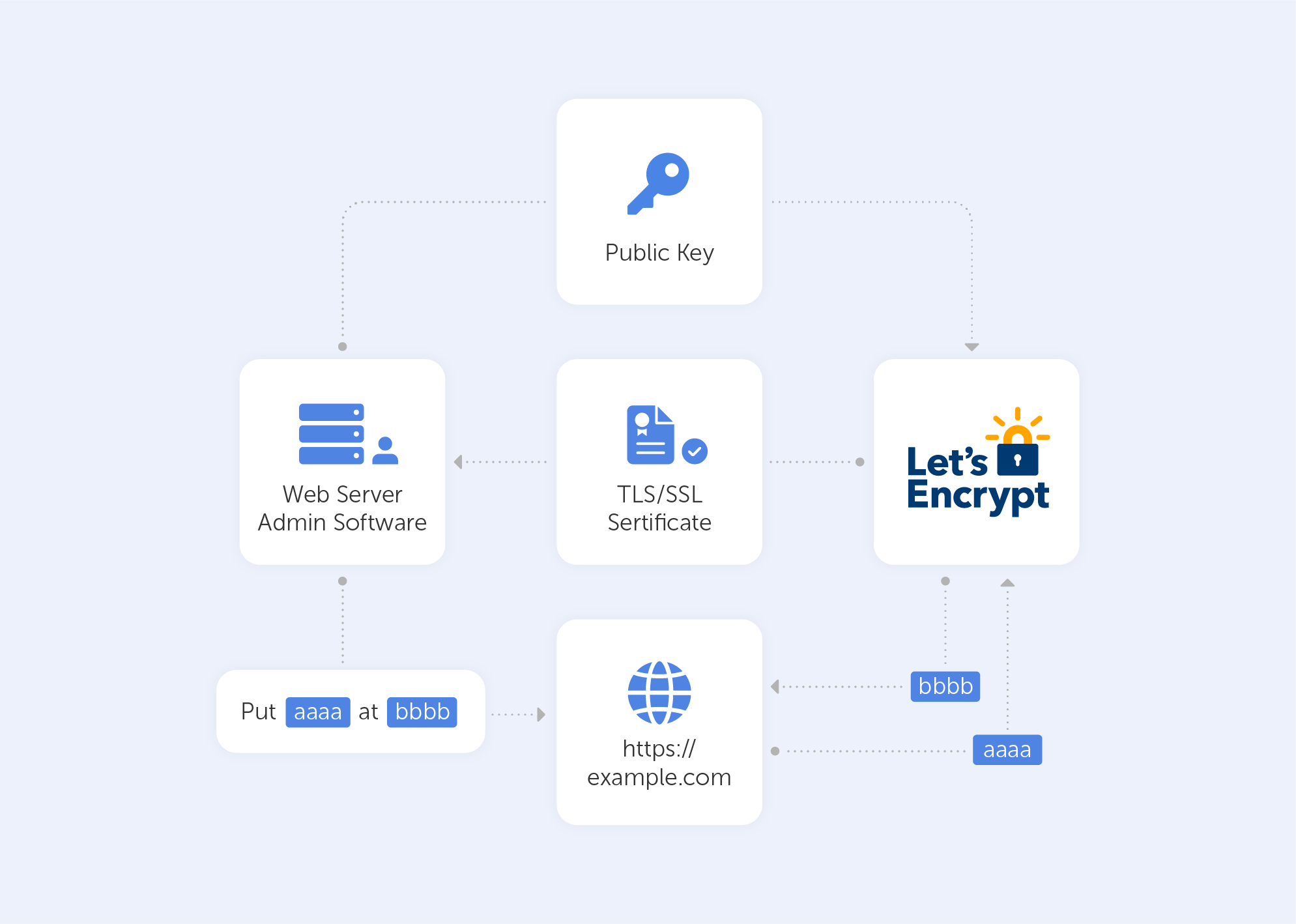

It provides free TLS/SSL certificates to any suitable client via the ACME (Automatic Certificate Management Environment) protocol. You can use these certificates to encrypt communication between your web server and your users. ‘Let's Encrypt’ provides two types of certificates. Single-domain SSL and Wildcard SSL, which covers a single domain and all of its subdomains. Both types of SSL certificates have a 90-day validity period. These domain-validated certificates do not require a dedicated IP address. They accomplish this by delivering the client a unique token and then retrieving a key generated from that token via an HTTP or DNS request.

There are dozens of clients available which can be easily integrated with a variety of standard administrative tools, services, and servers. They also come written in a range of different computer languages.

We'll use the win-acme client in this tutorial because it's a basic, open-source, and constantly updated command-line application. It not only produces certificates but also automatically installs and renews them. And yes, this tutorial is for Windows users.

How does it work?

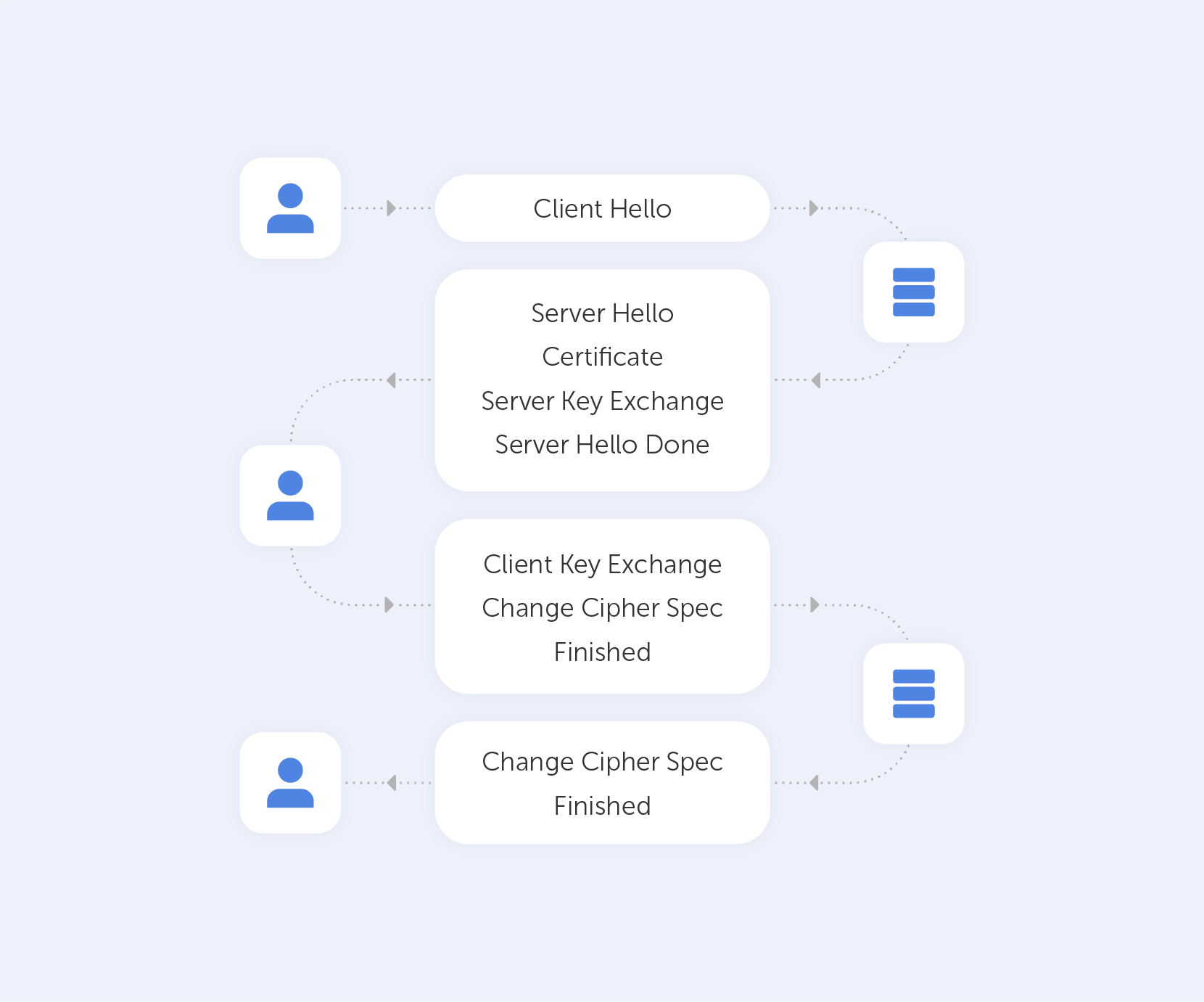

‘Let's Encrypt’ verifies the ownership of your domain before issuing a certificate. On your server, the Let's Encrypt client creates a temporary file (a token) with the required information. The Let's Encrypt validation server then sends an HTTP request to get the file and validates the token, ensuring that your domain's DNS record resolves to the ‘Let's Encrypt’ client-server.

In an HTTP-based challenge, for example, the client will generate a key from a unique token and an account token, then save the results in a file that the web server will serve. The file is then retrieved from the Let's Encrypt servers at: http://passwork.com/.well-known/acme-challenge/token.

The client has demonstrated that it can control resources on example.com if the key is correct, and the server will sign and provide a certificate.

How do I set it up?

Before we start:

- Make sure that you’ve downloaded the latest version of the application on the server from its Github release page;

- Scroll down to ‘assets’ and download the zip package named win-acme.v2.x.x.x.zip from the release page. If you're having difficulty with Internet Explorer, you may install Chrome on the server following this approach. Once the application has been downloaded, unpack it and save it somewhere safe for future use.

Now let’s Generate the Let’s Encrypt Certificates

Simply run wacs.exe to generate the Let's Encrypt certificates. Because we downloaded the application via the internet, you may receive a notification from Windows Defender claiming that "Windows protected your PC". Because of this, after clicking the "More Info" link, click the "Run Anyway" option. Because it’s open-source and widely utilized, the application is completely safe to use.

Follow these simple steps once the application has started:

- Choose N in the main menu to create a new certificate with default settings;

- Choose how you want to determine the domain name(s) that you want to include in the certificate. These may be derived from the bindings of an IIS site, or you can input them manually;

- A registration is created with the ACME server if no existing one can be found. You will be asked to agree to its terms of service and to provide an email address that the administrators can use to contact you;

- The program negotiates with the ACME server to try and prove your ownership of the domain(s) that you want to create the certificate for. By default, the http validation mode is picked and handled by our self-hosting plugin. Getting validation right is often the most tricky part of getting an ACME certificate. If there are problems, please check out some of the common issues for an answer;

- After the proof has been provided, the program gets the new certificate from the ACME server and updates or creates IIS bindings as required, according to the logic documented here;

- The program remembers all choices that you made while creating the certificate and applies them for each subsequent renewal.

For advanced instructions, visit this page.

And that’s pretty much it. It will successfully generate an SSL certificate for you if your domain is pointing to your server. It will also include a scheduled task that will renew the certificate when it expires. The SSL certificate will be installed automatically by the application.

Are there other options?

‘Certbot’ is the most widely used kind of ‘Let's Encrypt’ client. We didn’t give it much light in this article because it's “designed for Linux” and also a little more advanced. It comes with easy-to-use automatic configuration features for Apache and Nginx. And yes, there is a Windows version as well.

There are many other clients to choose from – the ACME protocol is open and well-documented. On their website, ‘Let's Encrypt’ keeps track of all ACME clients.

Here’s a list of the best options (n.b. most are for Linux):

- lego. Lego is a one-file binary installation written in Go that supports many DNS providers;

- acme.sh. Acme.sh is a simple shell script that can run in non-privileged mode and interact with more than 30 different DNS providers;

- Caddy. Caddy is a full web server written in Go with built-in support for Let’s Encrypt.

‘Let’s Encrypt’ is just great, there are no other ways to put it. It’s a free, automated, and open certificate authority, run for the public’s benefit. It can be accessed via a variety of tools and services. The best part is, they really keep their motto close to heart:

“We give people the digital certificates they need in order to enable HTTPS (SSL/TLS) for websites, for free, in the most user-friendly way we can. We do this because we want to create a more secure and privacy-respecting Web for all.”